What the Redux? (Part 2: The how)

Understanding Redux – properly.

May 29 2018

7 minute read

1257 words

This is a follow on from my previous Redux post – on why you might need to implement it in your application. This post explains how Redux works. There will be a third follow up post on implementing it with React.

Although it appears complicated, Redux is actually incredibly simple. No doubt looking at a complete application that implements Redux scares newcomers because of the amount of code needed to get going. A lot of tutorials go straight into teaching Redux with React. I'm going to explain how it works without React so we can understand the fundamental principles behind it.

Overview

Before I start I'll reiterate one thing - state cannot be changed. It is immutable. To change our data, we return a copy of our state.

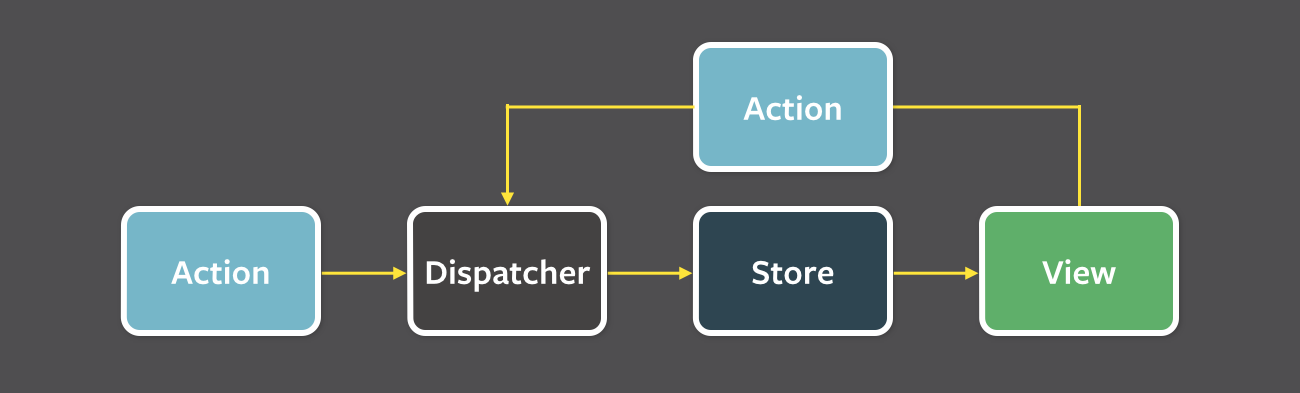

Redux's data flow is very simple. As seen in the flow diagram below.

Steps

- An action is dispatched on the store (this can be from the view, or from somewhere else)

- The dispatcher (abstracted by Redux) dispatches that action by passing it to all the reducers on your store

- Your reducers dictate how the state should be returned based on that action.

- State is updated

- The view is updated because the store changed.

I think the reason people are initially put off by redux is the order that it needs to be taught in. First you have to learn what an action is and a reducer - because without those we literally can't create a store. I'm going to go against the grain slightly and put an example of creating a store below - I won't go into it until later on though. Who knows, maybe this will help.

You'll see that it really does need a reducer to get going.

import { createStore } from 'redux'

import postReducer from './reducers/posts/'

const store = createStore(postReducer) // create store takes one reducer or the return object of combineReducers()

Actions

- Actions are the only source of data to the store.

- Actions describe what will happen to the store.

- They DO NOT change any data.

- They are simply objects.

- Actions are dispatched.

This is an example of an action.

{

type: 'ADD_POST',

post: {

title: 'Hello world',

body: 'This is the post body'

}

}

The only property needed on an action is type. Redux enforces this. You will use it on your reducers to decide what will happen to your state.

The above is a completely valid action. However, what we usually do is create action generators. These are simply functions that return an action object. This way we don't have to keep manually defining our actions, which will open us up to a lot of problems, mainly spelling mistakes in our types.

Below is the action generator for our action.

const addPost = post => ({

type: 'ADD_POST',

post,

})

// We wrap our curly braces in parenthesis so that the runtime evaluates the expression, as opposed to considering it our funciton block

We implicitly return an object from the function, our data will get passed in as an argument. We can now dispatch this action anywhere we like.

When we have a store we can dispatch this action like so:

store.dispatch(

addPost({

title: 'Hello world',

body: 'This is the post body',

})

)

This differs from traditional flux where you would usually dispatch an action within the action generator.

Reducers

The next step is reducers. We need to be able to deal with the action we just created. Actions get passed into all of our reducers by Redux.

- Reducers describe

howour data will change. - Redux will pass it two arguments:

stateandactionwhen you dispatch an action. - It does NOT mutate the state, instead it returns a copy of our state. This means we can view our state's history, across our whole application.

Below is a reducer that can handle our ADD_POST action. We have a default state set as an empty array as our posts will be an array of objects.

export default (state = [], action) => {

if (action.type === 'ADD_POST') {

return [...state, action.post]

}

}

Using the ES6 spread syntax (same as Array.prototype.concat()) we can return a new array with the new post on it. Remember, the post data is on the action itself, along with the type.

Eventually we will have a lot of actions to handle, so we refactor to a switch statement as it's cleaner than a bunch of if else.

export default (state = [], action) => {

switch (action.type) {

case 'ADD_POST':

return [...state, action.post]

default:

return state

}

}

Our default case will just be to return the state.

In a multiple reducer context, the state we return is the state relating to that reducer only. Defined, in our combineReducers() definition.

E.g.

combineReducers({ posts: postsReducer })

The postsReducer above will only have access to the posts on the store. Nothing else. When an action is dispatched our store will be an object with posts on it. store = { posts: [...] }

Store

We now have a working action and a reducer to handle it. We can now create a store. Redux gives us the createStore(reducer) function which takes a reducer and gives us the store object. We can pretend we've put our reducers and actions in separate files. I'd recommend having this structure or similar.

- store

- index.js

- actions

- posts.js

- reducers

- posts.js

// store/index.js

import { createStore } from 'redux'

import postsReducer from './reducers/posts'

const store = createStore(postsReducer)

We now have a store, we can dispatch actions on it.

// import { addPost } from './actions/posts

store.dispatch(

addPost({

title: 'Hello World.',

body: 'post body',

})

)

To read from the store we can use store.getState() .

Let's also subscribe to the store so that every time it changes we can see the result. store.subscribe takes a handler function which gets called every time the store changes.

store.subscribe(() => {

console.log(store.getState())

})

Our state will look like this. An array with our only post on it.

;[

{

title: 'Hello World.',

body: 'post body',

},

]

Right now we just have one reducer, but most applications will need more than one. To do allow this redux gives us combineReducers

In a multiple reducer context, the state we return is the state relating to that reducer only. Defined, in our combineReducers() definition.

// store/index.js

import { createStore, combineReducers } from 'redux'

import postsReducer from './reducers/posts'

const reducers = combineReducers({

// the state passed to postsReducer will be posts only.

// If we had a user property and reducer - that would not be passed in.

posts: postsReducer,

})

const store = createStore(reducers)

The store acts almost in the same way except it will now have the posts property on it, which will have our array of posts.

This is redux in a nutshell. Below we will go over asynchronous redux actions - as they're a little more involved.

Async actions

An asynchronous action returns a function which itself dispatches an action.

Flow

- Dispatch async action

- Function inside does some async work, networking or I/O

- calls

dispatch()on another action to update the store.

Redux doesn't support dispatching other actions out of the box. We can use the middleware redux-thunk which is tiny and very simple. It's literally 14 lines of code. To apply middleware we need to use applyMiddleware from redux. redux-thunk let's us return a function from an action generator, it supplies dispatch and getState as arguments to that function - meaning we can use them in our actions.

A thunk in JS is a function that wraps an expression to delay its evaluation. Source

In other words, a redux thunk is a function that wraps up a call to dispatch, calling it whenever you like. E.g. after an asynchronous process.

Our store initialiser becomes...

import { createStore, combineReducers, applyMiddleware }

import thunk from 'redux-thunk' // yarn add redux-thunk

import postsReducer from './reducers/posts'

const reducers = combineReducers({

posts: postsReducer

})

const store = createStore(

reducers,

applyMiddleware(thunk)

)

Now we're ready to write our async action.

Say we wanted to add our posts data to a database. We're going to pretend we've got an API that let's us add posts to a database. The fake endpoint will be api.site.com/posts, which we will POST our data to.

Our original ADD_ACTION remains the same.

Our new async action. It's common practice to prefix our async actions generators with start e.g. startAddPost

export const startAddPost = post => {

return dispatch => {

// we also get getState in the second arg.

fetch('https://api.site.com/posts', {

method: 'POST',

body: JSON.stringify(post),

// rest of stuff - use your imagination

})

// success

.then(() => dispatch(addPost(post))) // we dispatch our non-async action

// fail

.catch(e => console.error(e)) // do more here. Display an error etc.

}

}

There we have it, we've added a post to our fake database and then dispatched the normal action on success. On failure we could dispatch a failure action which updates our store saying we have an error or something. We could then display that in our view.

You might ask, 'if I have a component like PostLoop, why can't I just fetch the data in the componentDidMount() call?'. Well, you can, but you shouldn't. Our view layer should be concerned with as little logic as possible, it should be as presentational as we can make it.

I'm not looking for work at the moment but if

you have any questions feel free to get in touch...